The latest book I read for my book club was a dystopian novel, written by a Japanese author in 1994, that made me reflect about the current nature of our relationships – more specifically about how technology and social media have completely transformed our friendships.

The Memory Police & How Social Media Changed Friendships

Once a month I meet with a group of about 20 women on the second floor of the famed Parisian bookshop Shakespeare & Company. Louise and Camille are the co-founders of Feminist Book Club Paris, which was started about a year and a half ago: they select a book written by a female author, often with feminist undertones, and people interested in discussing it sign up for the event and gather to discuss it at Shakespeare & Company. It has fast become my favorite day of the month: I love how this book club is motivating me to read more and the community aspect of it – discussing feminist literature in an intimate setting with other women – is truly energizing.

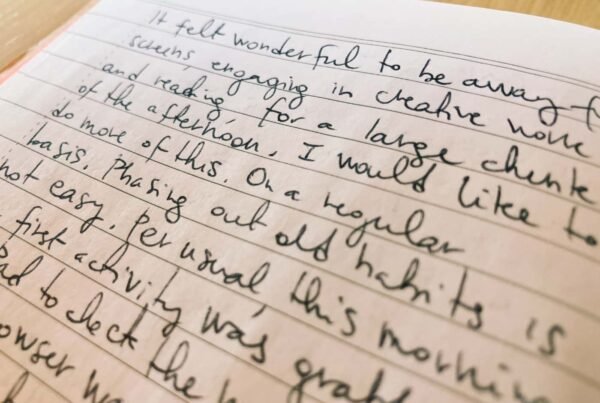

December’s book was Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, a dystopian novel written in 1994 and just recently translated into English. It is hard to talk about this haunting book without spoiling plot points – even the synopsis written by the novel’s publisher reveals too much, in my opinion. This review in The New York Times does a good job at explaining the premise of the book, without giving too much away:

When Yoko Ogawa discovered “The Diary of Anne Frank” as a lonely teenager in Japan, she was so taken by it that she began to keep a diary of her own, writing to Anne as if she were a cherished friend.[…] Decades later, Ogawa transmuted her imagining of Anne’s world into “The Memory Police,” a dystopian novel that is Ogawa’s fifth book to be translated into English and which goes on sale in the United States this week. It takes place on a mysterious island where an authoritarian government makes whole categories of objects or animals disappear overnight, wiping them from the memories of citizens.

When the Memory Police decides to make an object disappear, people on the island immediately destroy every copy of it – and they soon forget about its existence, so when the object is mentioned, the islanders have no idea what the word means. There is a minority of people who remember the objects and their disappearances and they are hounded by the Memory Police. Remembering objects that have disappeared is a dangerous thing.

Now, discussions about Ogawa’s The Memory Police often mention how it may be an allegory of the rise of authoritarianism and police surveillance. Others make reference to the role of memory in post-war Japan. The New York Times reviewer explains:

In Japan, where history itself has been subject to revision — and those who bring up the country’s wartime past can be denounced or even censored — the novel’s lament for erased memories could be read as veiled criticism.

Thing is, you do not have to live under an authoritarian regime to be able to identify with the characters from the Memory Police. While reading this suspenseful novel, I would often think about the things we have lost due to technological progress and the rising influence of social media and tech platforms on every aspect of our lives: how we now cultivate friendships, how we shop, and even how we date. Most of those activities, which used to take place in the real world, away from screens, have now moved online. And it’s as if we’ve collectively forgotten how they used to be. Powerful corporations are now exercising an outsized influence on those activities, behind the walled garden of their platforms. The change in our socialization is particularly worrying to me, because in a day and age where we can connect instantly, to anyone in the world, for free, at the touch of a button, we are also witnessing an epidemic of loneliness. How is this possible?

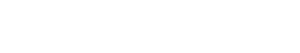

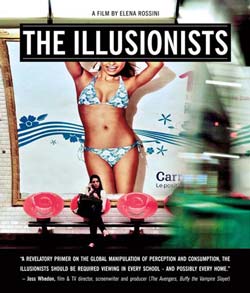

Well, platforms like Facebook and Instagram (owned by Facebook) provide the illusion of closeness: on the surface, they purport to connect people, but in reality, their business model is based on keeping users online, scrolling, clicking and typing for as long as possible, in order to extract data from them… that can be used to serve these users targeted advertising. We are “Alone Together” – like author and professor Sherry Turkle explained in a book by the same title. By design, these tech platforms are offering a kind of socialization that pales in comparison to face-to-face meetings with friends.

Have you ever heard of “parasocial relationships”?

Business editor and media advisor Heidi Moore posits that most of our online friendships could be in fact “parasocial relationships” in a brilliant conversation with author J. Kelly Hoey on the podcast Build Your Dream Network (starting at: 32:16):

Your energy has to be present. This is my current kick, I’m actually on a Twitter break because I want to really reconnect with the people that I know in real life. There’s a different energy to being present. And I think no matter how good you are online, at social media, there’s another concept that I find very compelling and it’s called “parasocial relationships.” It used to apply mostly to celebrities. A parasocial relationship is a unidirectional one. So you have a relationship with the person’s image. So you are seeing pictures of them, you’re seeing videos of them, and you feel like you know them and that you can relate to them. And that used to be limited to celebrities, that’s why we have celebrity journalism. But now I think, my theory is, we all have parasocial relationships to each other. We all see each others’ images and videos and we’re interacting with that curated form of them more often, most of the time, than we’re interacting with their true presence. And there is a lot to be said about just the sheer human moment of connection, of reading body language, of eye contact, of waiting and pausing, not just typing things into a little phone to ghosts you can’t see. And so I think if we take that as a cautionary tale – the idea that we don’t want to get into parasocial relationships with the people that we actually know – then it reminds us that it is very valuable to be present and to bring the full force of our focus and understanding. We learn from each other.

I stopped using Facebook and Instagram two years ago for this very reason (in addition to protesting against surveillance capitalism). To me, it had always felt awkward to type what I was doing in a little box on my computer or smartphone, and wait for reactions from my friends and acquaintances in the form of likes or comments. Instead of making me feel good and energized – like a real face-to-face meeting with a friend would – I’d feel a little anxious, checking back to see if friends had reacted to my post. And if they hadn’t, I would feel a tinge of disappointment, as if they didn’t care about me. I find it a little embarrassing to admit this because typing it out and re-reading it immediately shows how immature this sounds.

Thing is, I belong to the last generation that saw what life was like before social media became mainstream: Facebook was born when I was already out of college. I think about this often. To put things in perspective, television became mainstream in the U.S. in 1952. So adults born in the 1920s and 1930s, who up until that point only had radio as a means of mass communication, witnessed a sea change when television came along. Up until then, they could only see moving pictures at the cinema. Now those images were in their living rooms. Similarly, I do remember what life was like pre-internet. I was just a child, so those memories are fading, they feel like a distant dream. Yet, I do remember how as a teen, up to my college student days, I would spend hours on the phone each day with my closest friends. I would make sure to set up meetings to see those I loved, face to face, in real life, every day. When Facebook came along, I enjoyed the convenience and immediacy of it. And I didn’t pay attention to how the digital socialization it enabled paled in comparison to a phone call or a face-to-face meeting. I’m almost ashamed to admit the following but for the better part of a decade, most of my interactions could have been classified as “parasocial relationships.” One way. Unidirectional. Mediated by a screen.

We may not be living under the rule of an authoritarian Memory Police, but there are strong societal pressures to maintain social media accounts. Two years after leaving Facebook, I still have to justify myself when I meet a new person and tell them I don’t have an account. Their reaction is often furrowed brows. And don’t get me started about Instagram. Telling people I have neither a Facebook NOR an Instagram account makes me feel like a Martian sometimes. But I have no regrets: my life and relationships have greatly improved since leaving those platforms.

Sometimes I feel like one of those characters from Ogawa’s novel who remembers objects that have disappeared. And make no mistake, this is no humble brag. I am not claiming one state is superior to the other. Because both groups – those who remember and those who don’t – both live under the rule of the Memory Police. And life on Ogawa’s fictional island – a life that is constantly diminished by disappearances – has become absolutely normalized. Both groups suffer and are unable to communicate and truly relate to each other.

Back to the real world, I feel that modern relationships that are mediated by screens and social media platforms, these parasocial relationships, are now the new normal. And maybe this blog and The Realists documentary are my little act of resistance, my attempt at bridging the gap between two groups: those who remember what life was like pre-social media and those who don’t. I do remember. And I’d like to remind others of how things used to be, what certain platforms have taken from us, and that ultimately capital “F” Friendships take work and time. Beyond screens.

In the first interview for The Realists documentary photographer Sara Melotti said “I think we’re forgetting how to be human.” We don’t have to.